Crunchety Crunch

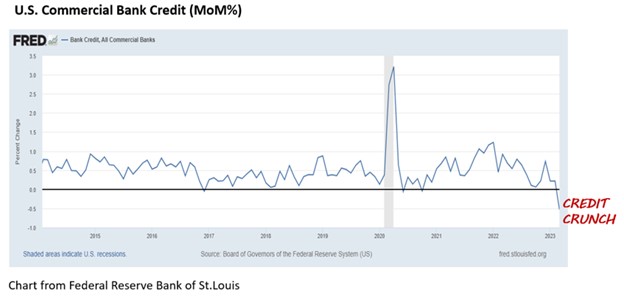

The credit crunch continues.

The European Central Bank published its Euro Area Bank Lending Survey (BLS) for the first quarter this week and it provides further evidence that the supply of, and demand for, credit is drying up. This is the headline paragraph from the report:

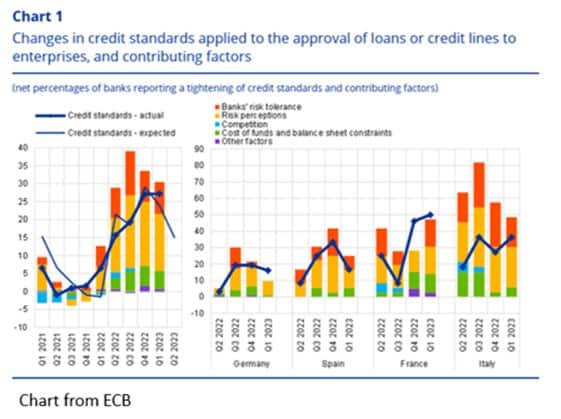

“In the April 2023 BLS, euro area banks indicated that their credit standards for loans or credit lines to enterprises tightened further substantially in the first quarter of 2023. From a historical perspective, the pace of net tightening in credit standards remained at the highest level since the euro area sovereign debt crisis in 2011. The tightening was stronger than banks had expected in the previous quarter and points to a persistent weakening of loan dynamics. Risks related to the economic outlook and firm-specific situation remained the main driver of the tightening of credit standards, while banks’ lower risk tolerance also contributed. The tightening impact of banks’ cost of funds and balance sheet situation on credit standards for loans to firms remained contained and broadly unchanged compared with the previous quarter. In the second quarter of 2023, euro area banks expect a further, though more moderate tightening for loans to firms.”

Lending standards also continued to tighten for housing and consumer loans, whilst demand for loans continues to drop with higher interest rates the main factor cited.

So, the ECB should be happy, right? This is what it wants to slow the economy and curb the rate of change in consumer prices. This, plus the stable consumer price inflation figures for April, will probably mean the ECB only hikes its policy interest rate by 25-basis points tomorrow. A 50-basis point hike would now be a shocker.

The thing is, though, the ECB cannot control what risk committees in commercial banks are thinking. The histogram in the chart below shows the net percentages for responses to questions related to contributing factors in relation to decisions on lending standards. This is defined as the difference between the percentage of banks reporting that the given factor contributed to a tightening and the percentage reporting that it contributed to an easing.

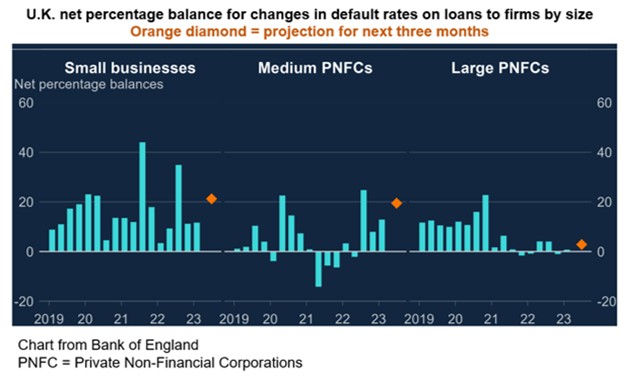

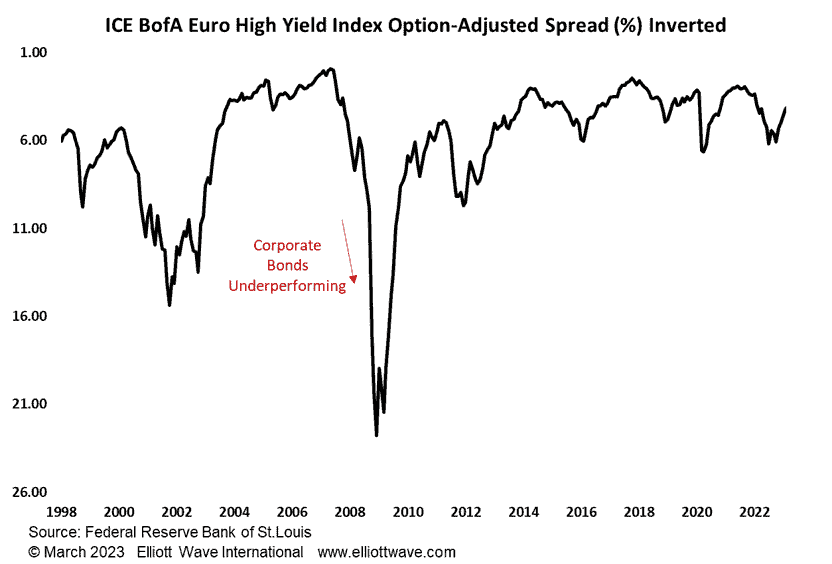

We can see that it is overwhelmingly risk perceptions and tolerance which drive decisions on lending standards, and with corporate credit spreads yet to really widen, the worst of the downgrade and default cycle looks to be still ahead of us. Money market futures are already pricing in an interest rate cut from the ECB by the middle of next year. If, as we suspect, stock markets continue to decline, that pricing of cuts will very likely be brought forward in time.