Anchors Away! Deficits, “Inflation” & Deflation

Yes, it’s all mood-driven, but our choices matter. And our choices on dealing with the “war on Covid” might be changing the global economic landscape.

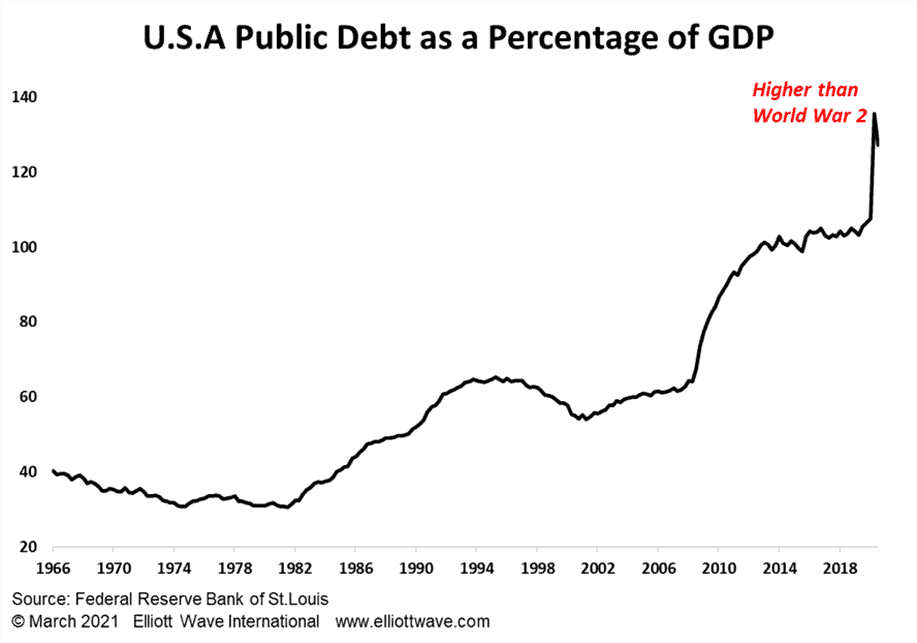

Government responses to the Covid-19 pandemic have been likened to wartime. Rationing (remember the great toilet paper rush?), civil liberty restrictions and emergency, unscrutinized legislation have become normal over the past year. But the 800-pound gorilla in the room is, of course, the eye-watering increase in public debt.

When the history books are written, no doubt many will take the opinion that governments really didn’t have a choice. They had to lockdown the economy because of a public health crisis and so they were morally obliged to provide economic stabilizers for the private sector. Governments always have a choice, but that’s a debate for another time. Now that public sector budget deficits have gone from massive to humungous, we need to think about the implications.

This recent paper titled, “Do Enlarged Fiscal Deficits Cause Inflation: The Historical Record,” by Michael D. Bordo and Mickey D. Levy for the National Bureau of Economic Research, examines whether large public sector budget deficits have, in the past, subsequently been associated with upwardly accelerating prices in consumer goods and services, or “inflation” as it is commonly known and consumer price inflation as we, more accurately, refer to it. The authors looked at the data from major economies since the 1800s and came to a few conclusions, summarized by us here:

- Whether it is occurring during wartime or peacetime is a key determinant of the connection between fiscal deficits and consumer price inflation.

- Dominance of the central bank by the fiscal authorities has led to accelerating consumer price inflation.

- Anchoring of expectations is important.

When governments have financed wars via a complicit central bank’s printing press, it has generally led to higher consumer price inflation. Given the “war on Covid,” is what we face now a similar situation? It very well might be.

Anchoring of inflationary expectations is perhaps the crucial aspect to focus on. Once that genie is out of the bottle, it becomes increasingly difficult to put it back in. Is the Fed playing with fire then by not only providing a magic money tree for the U.S. government, but also telling the market that it is not concerned about higher growth rates in consumer prices? It could well be.

Accelerating prices of consumer goods and services does appear to be an increasing risk. However, the crucial element is employment. So-called “cost-push” inflation has historically been associated with tight labor markets, not least in regard to unionisation. Can collective bargaining come back? Well, the “gig” economy ,which has kept wages relatively low, might be changing – witness a recent ruling in the U.K. whereby Uber have to treat their drivers as employees, with all the associated rights to sick pay, pensions etc.

In the end, though, these off-the-charts budget deficits that have been established are not sustainable. Funding a structural budget deficit via the money printing press, which is what the Modern Monetary Theorists advocate, works only to the extent that confidence is maintained in the currency. Confidence is not fixed.

Debt must be repaid (higher taxes / drag on growth), inflated away (via nominal growth / higher consumer prices) or defaulted on. Under all circumstances it results in debt deflation. It’s time to choose our poison.