Inflation, Deflation & Borrowers.

High consumer price inflation is good for borrowers, right? Err…

The Nasdaq index has now declined by more than 10% from its November high, prompting the mainstream financial media to call it a “correction,” whatever that means. I think they call it a bear market when it is down by 20%. Many stocks have already fallen by at least that amount, and realistically, it’s all semantics anyway.

It’s early days, but what is curious, though, is that high yield, or junk, bonds continue to hold up. To be fair, junk bonds, as measured by the U.S.$ CCC & Lower-rated yield spread reached peak outperformance in June last year and have underperformed since, but yet there have been no signs, as yet, of any rush out of the sector.

I heard an analyst on Bloomberg TV this week say that he was bullish of credit, particularly junk, because it does well in an accelerating consumer price inflation environment. The theory is that higher consumer price inflation means that companies can increase prices, thereby increasing revenue in nominal terms. At the same time, though, the amount the company owes via its bonds remains the same, thereby decreasing the debt’s real value and making it easier to service. It’s a win-win situation apparently, and that means junk bonds outperform.

The opposite should be true under consumer price deflation. Junk bonds should underperform because, with nominal corporate revenues declining, the value of debt goes up in real terms, making it harder for corporates to service it.

OK, I thought, channeling Mike Bloomberg’s mantra of, “in God we trust, everyone else bring data,” let’s have a look at the evidence.

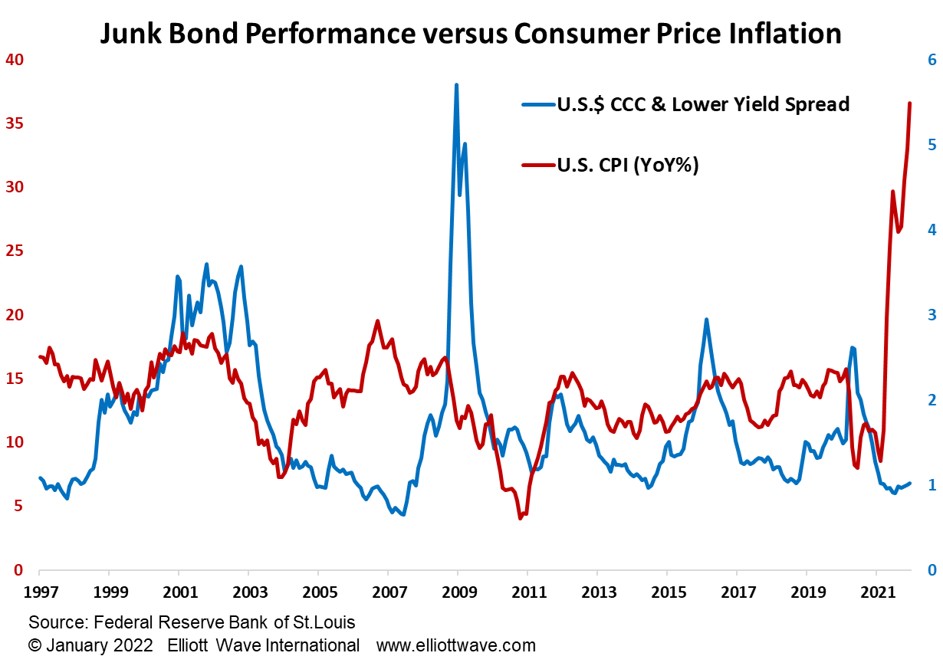

The chart below shows the U.S. dollar-denominated CCC & Lower-rated yield spread versus the annualized rate of consumer price inflation in the U.S. Apart from the period of 2004 to 2006, there’s hardly any evidence to suggest that accelerating consumer price inflation is good for the high-yield corporate debt market.

Junk bonds were only just being invented by Michael Milken in the 1970s, and didn’t come into popularity until the 1980s, but we can examine corporate bond performance by looking at the Moody’s Seasoned Aaa Corporate yield spread to U.S. Treasuries. Doing so, reveals that, in the first major consumer price inflation spike, between 1973 and 1975, corporate debt underperformed as the yield spread widened. In the second major consumer price inflation spike, from 1978 to 1980, corporate debt briefly outperformed but then underperformed dramatically, as annualized price inflation reached 13%.

It goes without saying, of course, that this analysis is just looking at the relative performance of corporate debt under accelerating consumer price inflation. The nominal performance is another matter. Borrowers and lenders (bond investors) both got savaged in the 1970s with the Moody’s Seasoned Aaa Corporate yield rising from 3% to close to 12%.

The conclusion we must reach is that the level of consumer price inflation does not matter to relative corporate bond performance. It does, however, matter for nominal performance. More semantics, some may say. What really matters is how it affects one’s wallet.