The Debt Deflation Illusion

U.S. households have been reducing debt since the Great Financial Crisis of 2008. Or have they?

The explosion in public sector and corporate debt over the course of World War C has grabbed all the headlines but, for households, it’s been a rather different story.

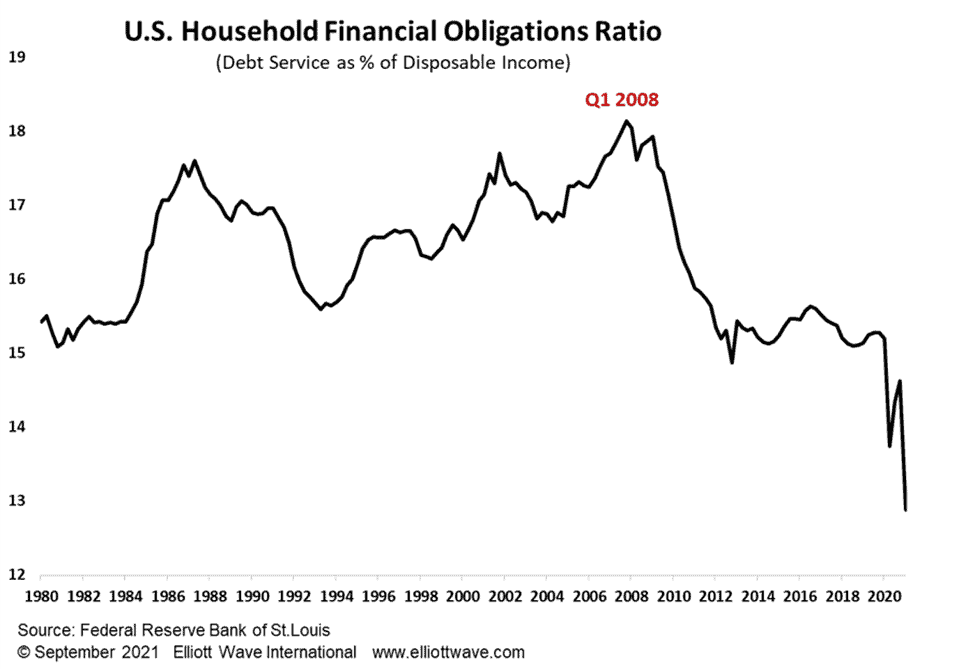

The chart below shows a measurement of U.S. household debt as a percentage of disposable income, also known as the Financial Obligations Ratio (FOR). From Investopedia:

“This measure, which is intended to capture the share of household after-tax income obligated to debt repayment (such as mortgages, HELOCs (Home Equity Line of Credit), auto loan payments, and credit card interest), is calculated as the ratio of aggregate required debt payments (interest and principal) to aggregate after-tax income. It is the only national economic measure of the burden of household debt and other obligations on household budgets.”

As we can see, the FOR has plunged into the latest data point (Q1 2021) of 13%, indicating that households are reducing their debt obligations relative to their income. On the face of it, it looks like debt deflation is accelerating.

But hold on. Let’s think about this. Look at when the peak occurred – 18% in Q1 2008. One the one hand, that would back up the thesis that, for individuals at least, the mood trend which produced the “shock” of the Great Financial Crisis has led to a seeping conservatism over the past decade-plus.

On the other hand, though, short-term interest rates were much higher in 2008. The Fed Funds rate was at 4% in Q1 2008 and then plunged to effectively zero from 2009 to 2016. It meandered up to over 2% by 2019 but has collapsed again to zero. What has been happening is that the interest on household debt has evaporated in the free-money era and that has had a significant effect on this measurement. The nominal stock of consumer credit deflated slightly in 2009 to $2.5 trillion but, since then has inflated to over $4 trillion. In other words, the debt is much higher but is less of a burden relative to income because the cost of carrying that debt has disappeared.

Far from being a positive sign, this is reason to open our eyes even further. Should interest rates now rise, the debt burden will become unbearable very quickly and a proper debt deflation will occur. This fact, some people say, is the reason why interest rates cannot rise. Well, the Fed might be caught in a trap over the Fed Funds rate but that won’t stop open market interest rates from rising. We’re watching the short end of the yield curve like hawks.